Evan Jones, University of Bristol (8 Dec 2025) 10 min read

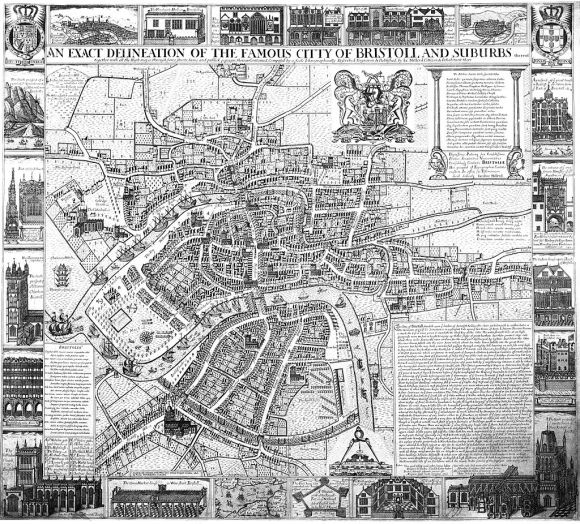

James Millerd’s 1673 map of Bristol is the best known and most widely used representation of the pre-modern city.1 When Bristol Museum and Art Gallery acquired the only surviving copy of the first edition in 1922, the Keeper of Maps at the British Museum, said of it:

This must, I think be one of the most valuable documents you have in your public archives. So far as I know there is no plan of any other town in the Country, at that period, on the same scale and with similar interesting and valuable pictures in the margin.2

Despite the fame of his map, James Millerd has been little researched and his topographic works rarely analysed in depth.3 Given that his map is so well known, it might seem to be an odd topic for a series of Stories that are about working in the archives. Yet, it illustrates the rising importance of the ‘digital archive’ and the way that digitisation does not just make historical research easier: it encourages us to examine old documents in new ways.

This story concerns four jokes, all in Latin, embedded in Millerd’s map. As far as I’m aware these have received almost no discussion to date: Millerd as a humourist is a novelty. And it was certainly new to me, despite having had a copy of his famous 1673 map hanging on my office wall for three decades.

I only noticed Millerd’s first joke a year ago, while working on another BRS story, Locating Bewell’s Cross. Investigating the Cross and the associated gallows, prompted me to think more closely about what Peter Fleming (UWE) described as Bristol’s ‘Via Dolorosa’.4 This was the route condemned prisoners walked from Newgate gaol to the gallows: a walk that reflected the processional route that Christ followed through Jerusalem to Calvary.

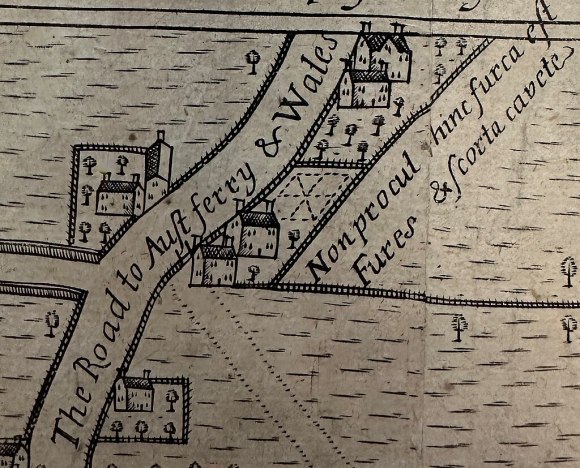

Millerd’s joke about the gallows takes the form of a Latin tag, next to ‘The Road to Aust Ferry and Wales’. That thoroughfare is St Michael’s Hill, with the tag located at the top of the steep slope where St Michael’s Hospital now lies.

Non procul hinc furca est

Fures & Scorta cavete

I first translated this as ‘Not far from here is a fork, watch out for thieves and prostitutes.’ The fork in the road lay just beyond the edge of Millerd’s map, where the mini-roundabout now lies, next to Cotham Church. So, Millerd’s note seemed to be a warning to travellers heading north out of Bristol. However, a colleague of mine, Gwen Seabourne in Law, then pointed out that ‘furca’ can also mean ‘gallows’ in medieval Latin. Another colleague, Ben Pohl in History, then observed that ‘fures’ and ‘scorta’ could be nominative, accusative or vocative plural in Latin, while ‘cavete’ is imperative. So the tag has a double, double meaning. It could be taken as a warning to travellers, but might also be read as a warning to criminals: ‘Not far from here is a gallows. Thieves and Prostitutes, watch out!’

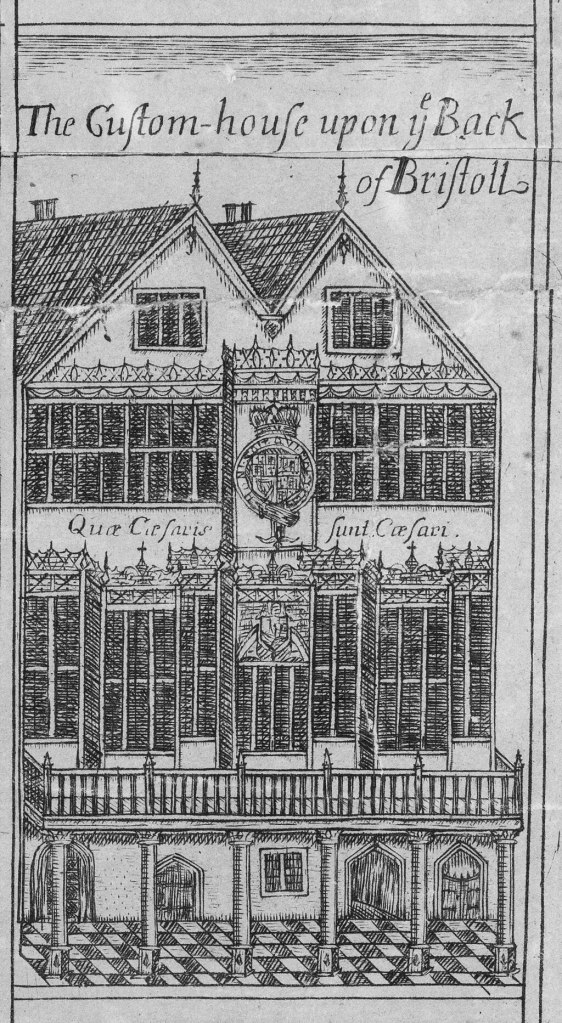

Millerd’s second joke is written on his marginal illustration of Bristol’s Custom House:

Quae Caesaris sunt Caesari

This is a variation of the passage from the vulgate Latin Bible, where Christ is asked whether it is lawful to pay taxes to the Romans. According the Testament of Matthew and Mark, he responded ‘Quae sunt Caesaris Caesari’ (Mark, 12:17; Matthew, 22:21). In other words, ‘Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s’.

The humour here is presumably that Bristol’s merchants were notorious for smuggling and other forms of tax evasion. Having written a book on Bristol’s illicit economy some years ago, I was well aware of this.5 And matters were no better after the Restoration.6 In this context, I think we can take Millerd’s Latin joke as a dig at the city’s merchants, a group that he, as a draper (cloth merchant) , would have been very familiar. In effect, it is an injunction to the richest men of the city to ‘Pay your taxes!’

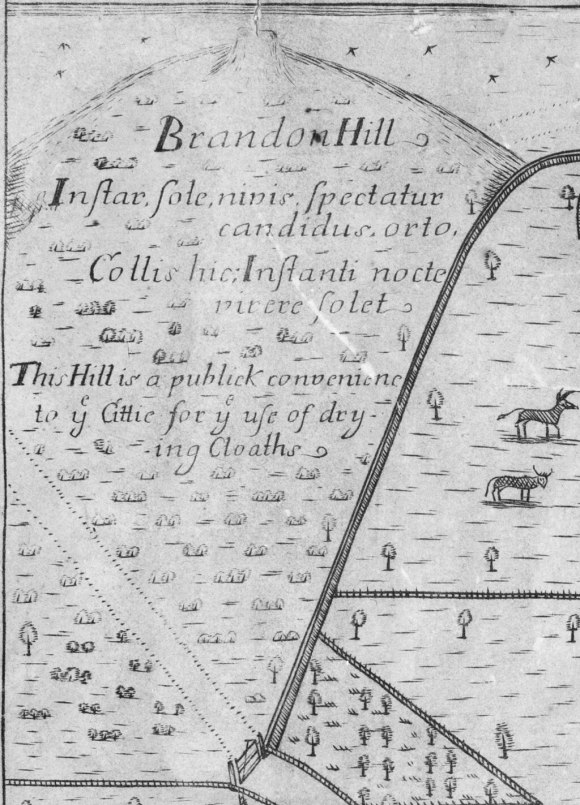

The third joke is the one I’m fondest of. I only spotted it very recently and it’s the one that finally convinced me to write this story. As with the others, I hadn’t noticed it, even though, once more, it is sitting on the map in plain sight. The insert concerns Brandon Hill:

Instar, sole, nivis.

Spectatur candidus, orto,

Collis hic; Instanti nocte

virere solet

The Hill is a publick convenience

to the Cittie for the use of dry-

ing Cloaths

While I guessed what the Latin text was referring to, I confess I needed two more colleagues to provide me with a precise translation – especially one that might tease out any erudite allusions. For this, I thank the classicists Ian Calvert and Ellen O’Gorman.

They translated the tag as:

In the very likeness of snow, this hill glows white at the rising of the sun, and is accustomed to become green with the coming of night

This is perhaps not so much a joke as a riddle. It is one that the English text provides the key to, but which would only be understood by someone who was very familiar with the city. The tag references the longstanding and much-exercised right of the city’s washerwomen to use Brandon Hill for drying clothes.7 The riddle implies this happened to such an extent that, seen from the city, Brandon Hill turned white during the day from all the laundry spread out to dry, but reverted to green at sunset, when the washing was taken in. It provides a wonderful glimpse of everyday life in the city and of its visual culture.

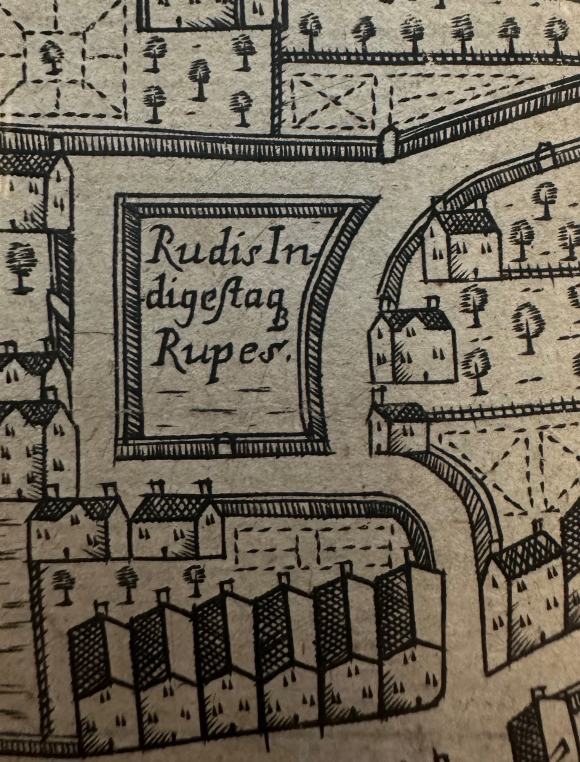

The last joke (or at least the last I’ve spotted), is perhaps the most erudite but, on the face of it, the least funny. Written in an enclosed piece of ground west of what is now Trenchard Street carpark are the words:

Rudis In-

digestaque

Rupes

This can be translated as ‘Crude and unorganized Rock’. I am not the first to notice this one. Indeed, Richard Coates (UWE) wrote about this ‘Millerd Mystery’ in an article about Bristol place names some years ago.8 He suggested the text alludes to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in the poet’s description of the primal chaos at the start of the universe, when all was ‘rudis indigestaque moles’ (crude and unorganised mass).9 Ian Calvert concurred with this interpretation, noting further that Metamorphoses was a basic Latin school text. Given this, anyone who was capable of understanding the Latin would probably get the allusion.

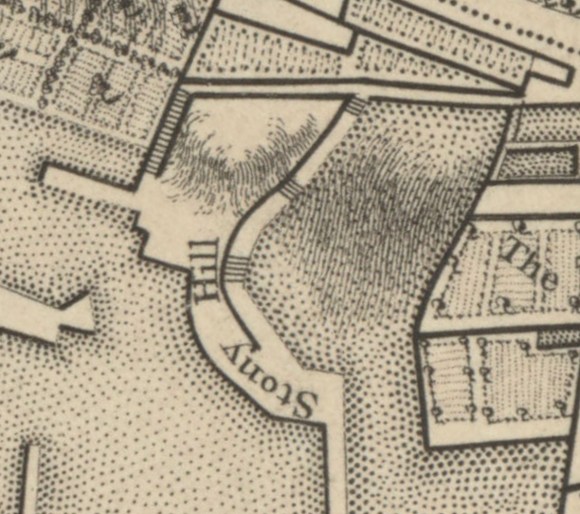

At first I hoped this nod to Ovid might be subtly referencing some nefarious activity going on in this enclosure. But it’s probably less exciting than that. The point about this piece of ground is that it was not a field or garden, as one might assume from Millerd’s map. Rather it was a very steep and rocky slope known as Stony Hill. This is best illustrated on Rocque’s 1743 map of Bristol, which marks the steps going up either side of the scarp.10

The plot was unoccupied until the late eighteenth century and, even after it was developed (following what must have been some serious civil engineering work), the street was still called Stony Hill, with its upper section sometimes referred to as Frogmore Cliff.11 Today the houses are gone and the whole slope of Stony Hill has been carved away. The ‘crude and unorganized rock’ is now a large block of student flats.12 However, climbing the long zig-zagging flight of steps from Trenchard Street up to Park Row, running along the eastern edge of Millerd’s enclosure, still gives you a sense of how steep this little bit of Bristol once was.13 Perhaps Stony Hill’s rocks and cliffs looked to Millerd like some primal leftover from the dawn of creation. Perhaps you had to be there…

So, those are my four jokes on Millerd’s map, in which he sought to humour his audience and impress the more literate. Apparently self-taught, the cloth merchant had turned himself into a skilled surveyor, cartographer and illustrator: producing an English city map that was the most sophisticated undertaken outside of London. If his little jokes seem like an aside to that endeavour, he can surely be forgiven them.

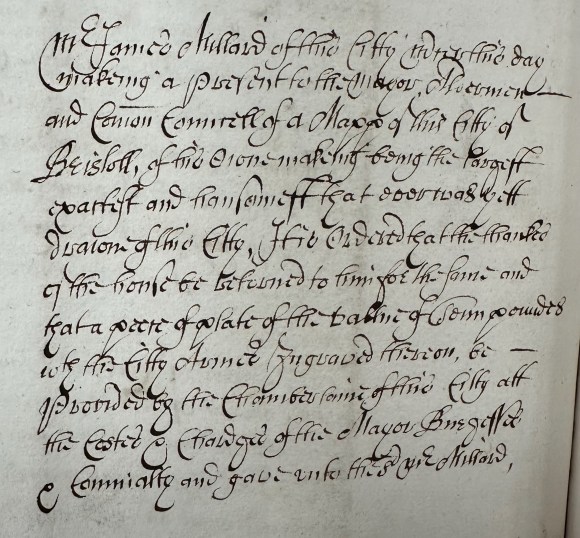

Fortunately for Millerd, both the City Council and the Society of Merchant Venturers saw value in the map.14 On 25 August 1673 he formally presented the map to the Council and they, in response, awarded Millerd their thanks and a piece of silverware, to the value of £10, with the city arms engraved on it. This was for his present of:

‘a Mapp of this Citty of Bristoll, of his owne makeing being the largest exactest and hansomest that ever was yett drawn of this Citty’.15

The silver plate would take the form of a tankard presented to him a fortnight later, most likely at the next council meeting.16 One presumes he liked a drink.

It seems that Millerd, buoyed by his success, then decided he would go further, producing a large engraving of the city as seen from the southeast.

This too mirrored the work done by cartographers and illustrators of London and other great European cities.17 Millerd may have hoped that Bristol’s authorities would take pride in seeing their own city so displayed. Apparently, they didn’t. This time there was no reward, recognition or official encouragement for Millerd to continue his endeavours. It was surely one of Bristol City Council’s more shortsighted decisions.

Millerd took his rejection poorly. If his response was humorous, it was a bitter humour. He returned to his copper plate and scraped out the dedication at the bottom. And Millerd, the draper, then drew drapes over his dedication. And for spotting those visual puns, I credit Jamie Carstairs, Digitisation Officer at Bristol University Library.

Millerd left just enough of his dedication visible that an educated person with Latin could readily tell that this was a humble dedication to his noble city, its council, its great men.18 But now, they’d never know! At the same time the winged head above the dedication was probably altered.19 Winged heads in such a place would be common for a cherub, but this is the face of an older man. And as my colleague Margaret Condon pointed out, his eyes are shut. Perhaps this is meant to be Millerd, then in his late thirties, telling the city that he would now be ‘withdrawing his gaze’ from Bristol. It was his last topographic illustration.

Bringing things up-to-date and returning to the theme of digital archives, the Bristol Record Society digitised and epublished the final (1728) edition of Millerd’s map in 2020, to make the map and its border illustrations freely available to all in high resolution.20 The same has now been done with Millerd’s prospect, using the copy belonging to Special Collections, University of Bristol Library.21 We hope that Millerd would have been pleased.22

References

- For their assistance, ideas and feedback while working on this story, I thank: Charlotte Berry, Ian Calvert, Jamie Carstairs, Richard Coates, Margaret Condon, Ellen O’Gorman, Francis Greenacre, Ben Pohl, Steve Poole, Gwen Seabourne, Nicky Sugar and Kath Thompson. ↩︎

- J. E. Pritchard, ‘A hitherto unknown original print of the great plan of Bristol by Jacobus Millerd, 1673‘, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 44 (1922), p. 220. ↩︎

- It was for this reason that I created a Wikipedia article on James Millerd, gathering together disparate material relating to his life available from published sources. ↩︎

- Peter Fleming, ‘Processing Power: Performance, Politics and Place in Early Tudor Bristol‘, in A. Compton Reeves (ed.), Personalities and Perspectives of Fifteenth-Century England (2012), pp. 148–149. ↩︎

- Evan T. Jones, Inside the Illicit Economy: Reconstructing the Smugglers’ Trade of Sixteenth Century Bristol (2012). ↩︎

- W. B. Stephens, The Seventeenth-Century Customs Service Surveyed: William Culliford’s Investigation of the Western Ports, 1682-84 (2012); Graham Smith, Smuggling in the Bristol Channel, 1700-1850 (1989). ↩︎

- John Latimer, Sixteenth-Century Bristol. (1908), pp. 58–59. For the popular local legend about how the washerwomen acquired this right, as well as the continuance of the practice till the late nineteenth century: J. F. Nichols, How to See Bristol (6th ed. (1893), p. 72. ↩︎

- Richard Coates, ‘Some Local Place-Names in Medieval and Early-Modern Bristol’, Transactions of the Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 129 (2011), pp. 190-91. ↩︎

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, 1, 7. ↩︎

- John Rocque, Plan of the City of Bristol (1743). ↩︎

- See especially the 1844-1888 OS edition, the 1894-1903 OS edition and the 1828 Ashmead map: ‘Know Your Place’, Bristol. ↩︎

- Orchard Heights, University of Bristol Accommodation. ↩︎

- The steps can be ‘walked’ using Google Streetview from Trenchard Street to the top of the steps and on to The Red Lodge on Park Row. The road along the top of Stony Hill is now blocked off. ↩︎

- For the Merchant Venturers reward: Patrick McGrath (ed.), Records Relating to the Society of Merchant Venturers of the City of Bristol in the Seventeenth Century (BRS, 17, 1952), p. 116. ↩︎

- ‘Common Council Proceedings, 1659-1675’, 28 August 1673: Bristol Archives, M/BCC/CCP/1/6, p. 248. I thank Bristol Archives for permission to reproduce this photograph. ↩︎

- ‘Mayor’s Audit book 41’, 11 September 1673: Bristol Archives, F/Au/1/42, fo. 50. ↩︎

- His most immediate comparators were probably the prospects of London by Anton van den Wyngaerde (1543), Claes Janszoon Visscher (1616) and Wenceslaus Hollar (1647 and 1666). ↩︎

- While none of the words are fully visible, enough is apparent that this was clearly a dedication in Latin, even leaving aside its placement and framing. Probable reconstructions include: ‘[Brist]oliae’, ‘pie[tas]’ (dutifullness), ‘[Anno] Dom[ini] (indicating the year of completion), ‘dedi[cat] (dedicate) and ‘[Mill]erd’. ‘Vir…’ at the beginning might be ‘Viris’ (To the men), or perhaps the start of ‘Virtute et Industria’ (Bristol’s moto). My thanks to Ian Calvert for this thoughts on this. ↩︎

- I thank Peter Dent (History of Art) for pointing out the wings on the head. ↩︎

- Bristol Record Society, Digitised Images. ↩︎

- We would particularly like to thank Nicky Sugar for supporting this project and Jamie Carstairs for doing the work. ↩︎

- Over fifty high-resolution jpg images (c.10 MB each) have been uploaded to Wikimedia. Links to them are provided from the BRS Digitised Images page, while ‘galleries’ of many of the images can be found on the James Millerd Wikipedia article. ↩︎