Dr Kathleen Thompson, University of Bristol (26 May 2025) 11 min read

In my childhood we often passed through Lawrence Hill railway station on the train to Temple Meads. When I came to study the history of East Bristol many years later, I realised that Lawrence Hill was originally St Lawrence Hill and took its name from a leper house or hospital dedicated to St Lawrence that once lay there. Leprosy, now called Hansen’s Disease, is a fearsome illness that left sufferers facially disfigured and paralysed. Worse still in the medieval mind it was seen as a punishment for sin so that lepers were obliged to withdraw from the community and live separately. Bristol even published ordinances that lepers were not to live within the town, and St Lawrence’s had been founded as a refuge for them in what was then a rural landscape to the east of Bristol.

This is a story about how the wealth of material preserved in Bristol Archives reveals that vanished landscape and tells us more about the history of the lost lepers of Lawrence Hill.1

Landscape

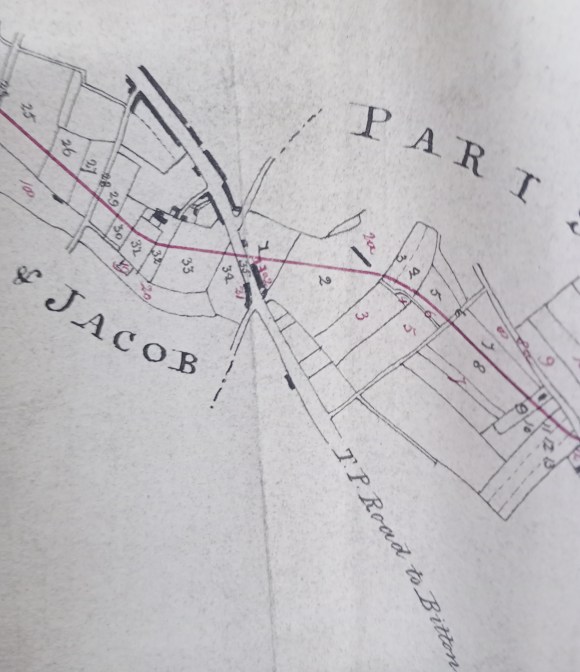

I started with the maps that had to be deposited with the Clerk to the Quarter Sessions when a new railway was projected. There is a map of Lawrence Hill (pictured right) that shows the area in the mid-1820s when a railway was about to be built from Coalpit Heath to the Floating Harbour. It shows a broadly rural landscape of fields and closes, mostly occupied by nursery gardens and pasture.2 Yet the name of Lawrence was still firmly associated with the area. I found a conveyance of 1784, for example, recording a sale of land that lay in Lawrence Leaze [BA 26764/2] to the north of the London road (described on the map as the turnpike road to Bitton), while another transaction of 1820 [BA 4965/24/h] mentions Lawrence Bridge. The bridge crossed the now culverted Wain Brook in the vicinity of the modern Ducie Road, an important clue to the site of St Lawrence’s because the watercourse would have provided bathing water that was one of the few medieval treatments for leprosy.

To locate the hospital more precisely I turned to the notes left by William Worcestre, who described his native city of Bristol in the late fifteenth century. He says that the hospital and its “beautiful church” lay on the London road half a mile from Lawford’s Gate. The beautiful church is long gone, but we know that remains were still there in the eighteenth century because the “vestiges of an old chapel” on Lawrence Hill were described by Samuel Rudder in his history of Gloucestershire published in 1779.

It was William Worcestre’s custom to measure distances in terms of his steps. In this case the hospital was 1200 steps from Lawford’s Gate, the ancient eastern gate of Bristol, which lay at the junction of modern Old Market Street and Midland Road. Its name survives in today’s Lawford Street. Measuring out William Worcestre’s 1200 steps places the site of the hospital under the modern Lawrence Hill roundabout, where the A420 and the A4320 intersect. This was the scene of extensive earth moving operations between the 1970s and 1990s as Bristol toyed with the idea of an urban motorway, so there was no scope for me to look for archaeological investigations.

Documentary evidence

In the absence of archaeological remains, what do the documentary sources tell us? We know from the records kept by the king’s Chancery in the twelfth century that St Lawrence’s Hospital was founded by King John before he became king, when his title was count of Mortain. John had married Isabel, daughter of the earl of Gloucester, and she had inherited her father’s lands, which included Bristol. It was John who, as count of Mortain, issued Bristol’s first surviving charter, the earliest dateable document in Bristol Archives. It was John too who took the lepers under his protection, giving them a small agricultural holding, a croft, outside Lawford’s Gate on the road that led to Bath and London. The location was important because it gave the lepers access to a busy main road, allowing them to beg alms from travellers. I looked in vain for records produced by the hospital, however. Although Bristol Archives holds the cartulary or record book of St Mark’s Hospital on College Green, whose church has become the Lord Mayor’s chapel, it has nothing from St Lawrence’s Hospital.

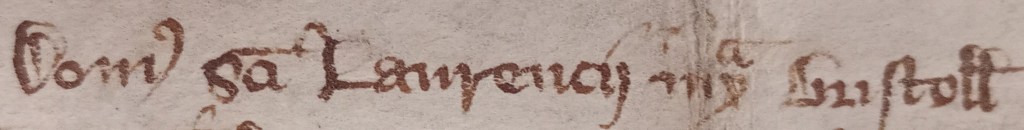

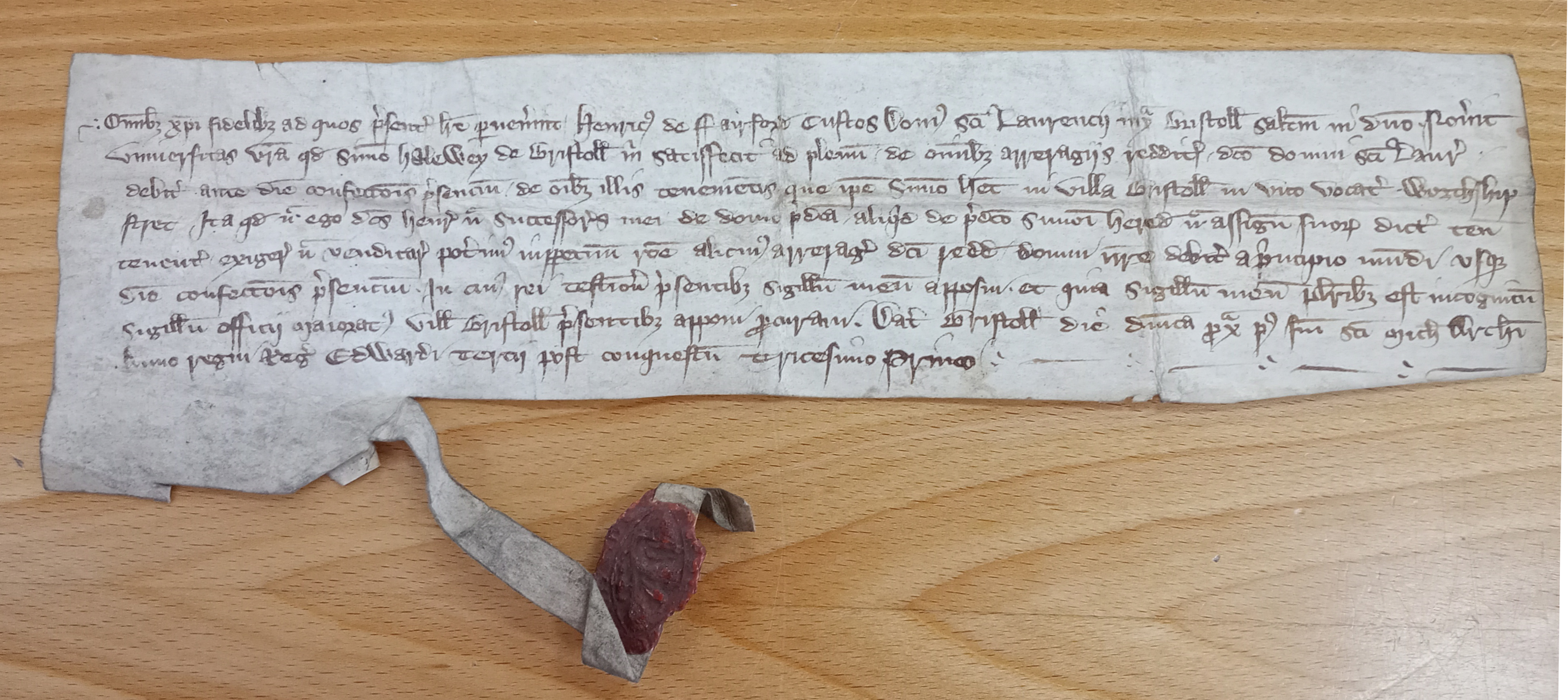

The Archives does hold, however, a document that is important for the history of St Lawrence’s (BA 26166/270). It is dated 1 October 1357 and it certifies that the Master of the Hospital, there described as the house (domus), Henry of Fairford, had received from Simon Halleway the arrears of rent owed on certain property. Henceforward neither he nor his successors at St Lawrence’s would make any further claim. The property was in Worthshipstret, a street later known as the Shambles, in the area between St Peter’s Church and Bristol Bridge where Bridge Street would later be laid out. We should not assume that the hospital owned it, however. It was not uncommon for people to devote a proportion of the rent from their property to religious institutions. We do not know the extent of the debt owed to the hospital, but we might speculate that it had accumulated in the difficult years after the Black Death had attacked England in 1348 and reduced the population significantly. Simon Halleway, who discharged it, was a rich merchant from a well-known Bristol family and he would have been keen to buy out any claims on the property because he was building up his interests in Worthshipstrete in the 1350s.

The donor’s seal is attached. It is now much worn, but it is vesica-shaped, that is a pointed oval, indicating that it belonged to a cleric. It is the only surviving seal from St Lawrence’s. The document also says that, in case Henry’s seal is not well-known, the seal of the mayoralty will be added, which would be an additional guarantee of the act. Unfortunately it is no longer there. This is quite a small piece of parchment but it tells us a great deal about St Lawrence’s. There is the name of the master and we see him managing the endowment that had been acquired to support the leper community. It is evidence for charitable giving among medieval Bristolians and indicates that, as well as its agricultural holding, the croft, St Lawrence’s also had urban interests, given by benefactors. Altogether, it is an important document and has had an adventurous life, as I was about to find out.

Wandering documents

Now that I had the name of a master of the hospital, I checked the Bristol Archives online catalogue to see whether there were other documents that included the name of Henry of Fairford. I found another entry for a certificate and release given by Henry of Fairford to Simon Halleway [P.AS/D/WSS/17]. It sounded remarkably similar to the one I had seen and it should have been among the records of All Saints Church in Corn Street. Unfortunately, it is missing and was missing when the records were deposited by the churchwardens between 1963 and 1977. The archivists know about its contents, however, because it appeared in a list made by All Saints’ parish clerk, George Tyndall, soon after 1748.3 Sometime in the intervening years it disappeared from All Saints’ vestry and had presumably been lost.

There was a ready market for deeds and documents of all kinds in the years before 1900. Sometimes their legitimate owners had sold them, but frequently they had been pillaged from organisations like All Saints’ parish vestry. Interest in the city’s history was growing and these documents were collected by antiquarians. The Maskell collection [BA 08153/1] illustrates how these collections could be made, broken up and change hands a number of times. It found its way into the hands of Francis Frederick Fox (1833-1915), a Bristol oil and colour manufacturer with antiquarian interests.4 When Alderman Fox’s library was sold in 1930, the album was purchased by the Town Clerk on behalf of the Corporation. By then the Record Office had been founded and it went straight there. Unfortunately there was limited resource to catalogue every item in the album and so its contents were hidden until a list was published by the Bristol Record Society in 2022.5

This made me wonder about the document that Bristol Archives had catalogued as BA 26166/270. Where had it come from? The Archives’ accessions records provide the answer – it was purchased in June 1967 at a Sotheby’s sale of items from the collection of Sir Thomas Phillips (1792- 1872), who has been described as “the greatest manuscript collector of all time”. The son of a rich cotton manufacturer, who bought his way into the landed gentry, Phillips had considerable resources and collected not only English manuscripts but also French material that came on the market after the French Revolution. Several county record offices have collections of material acquired since the dispersal of Phillips library, such as Gloucestershire Archives’ D4431 and Herefordshire Archive Service’s AH83.

Piecing together the story of the document, then, it appears that Simon Halleway, a Bristol merchant, was buying up property in Worthshipstrete, Bristol in the 1350s. He bought out an existing commitment to pay some of its rents towards the maintenance of the lepers at St Lawrence’s Hospital outside Bristol. The Master of the Hospital gave Simon a written undertaking that no further claims would be made. After Simon’s death his property came to his daughter, Joan, who had married a man with the same surname as herself, Thomas Halleway.6 It was Joan and her husband Thomas who established the Halleway chantry at All Saints Church in the 1450s with their son Thomas as its first chantry priest. Endowing a chantry was an act of piety by affluent citizens, which involved giving enough resources to fund a priest to say masses for the donor after his or her death, usually on a daily basis. The Master of St Lawrence’s document therefore came to rest in the vestry of All Saints (pictured below) with all the deeds relating to the property that supported the chantry.

It stayed there until the mid-eighteenth century when the parish clerk, George Tyndall, made his list. At an unknown date after that it was removed. We might speculate that the attraction was the mayoral seal, which had been added to the document, but is no longer there. A fine example of a civic seal would command a high price in the antiquarian market. The document itself had a price on that market too and was sold, eventually coming into the hands of Sir Thomas Phillips. Fortunately when there was a sale of Sir Thomas’ manuscripts in the 1960s it was purchased by the then Bristol Record Office, but it did not rejoin the All Saints’ archive. Instead, it was catalogued as part of a collection with the reference number 26166 ‘Deeds and documents belonging to Christchurch, City’. It is difficult to account for it being allocated to this collection since Christchurch did not and apparently never had owned property in Worthshipstrete. When the All Saints’ records were added to the catalogue they were all given reference numbers that reflected the parish clerk’s list, even the ones that were missing. The reference number P.AS/D/WSS/17 was given to the missing document at much the same time as the deed itself entered the Record Office, having been purchased at Sotheby’s, and was given the number 26166/270.

One further document in the city archives completes the story of lepers of St Lawrence. We know from royal records that Edward IV (1461-83) gave the site of St Lawrence’s Hospital and the endowments that had accumulated to the college at Westbury-on-Trym. The incidence of leprosy was probably falling and there were two other leper hospitals in Bristol. It seems a high-handed way to deal with a religious foundation, but worse was to come. After he had dissolved the monasteries in the 1530s, Henry VIII closed down smaller religious houses like Westbury. Its assets, including the site of St Lawrence, were sold at a bargain price to Ralph Sadler one of Henry’s courtiers (pictured left). The letters patent that record this gift may be consulted at Bristol Archives, AC/AS/1/1.

References

- I would like to thank Bristol Archives for permission to include images of their documents in this article and the searchroom staff and archivists for their help in uncovering this story. All images subject to copyright. For their comments on earlier drafts of this article, I thank Richard Coates, Margaret Condon, Evan Jones, Steve Poole and Jonathan Barry. ↩︎

- Bristol Archives, JQS/DP/1827a. ↩︎

- All Saints’ City Bristol Calendar of deeds part I, introduction and text, work submitted in part requirement for the London University Diploma in Archive Administration by P. L. Strong, July 1967, v. Copy available in Bristol Archives. ↩︎

- Irvine Gray, Antiquaries of Gloucestershire and Bristol (Gloucestershire Record Series, 12) Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1981, no. 44, p. 124. ↩︎

- The Maskell Collection: introduction and descriptive list of Bristol Archives 08153/1, ed. Margaret Condon and Evan Jones. Bristol Record Society Occasional publications, no. 5. ↩︎

- E. G. C. F. Atchley, ‘The Halleway Chauntry at the Parish Church of All Saints Bristol and the Halleway Family,’ Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 24, (1901) 74-125. ↩︎