Steve Poole, University of the West of England (12 April 2024) 14 min read

How do historians make archival discoveries? I’d like to say we carefully piece together connected pieces of evidence, contextualise them from a formidable storehouse of scholarly knowledge, then follow a rational deductive path to further sources and, eventually, arrive at something we might call historical knowledge. Sometimes that’s even what happens. But at other times it can be a more serendipitous process.1

This post is about serendipity in the archives; making chance discoveries and using a bit of background knowledge to place them into context. It’s also about the strange lure of historical objects and, in this case, the ways in which everyday things – a magnifying glass and an old woollen purse – have the power to connect us across the centuries to the lives of people just like ourselves. Victorian antiquarian collectors knew all about that and admitted no academic embarrassment in its pursuit. Take Richard Smith for instance, a man whose appetite for the antique was well known in the nineteenth century city.

Smith, senior surgeon at the Bristol Infirmary from 1812-1843, was certainly no regular sawbones. A familiar figure on the city streets, in his rough camlet cloak, his small white dog trailing behind him, Smith was ‘an indefatigable antiquarian’ in the eyes of the Times and Mirror, and ‘as a collector of “things ancient, curious, value-worth and rare,” few surpassed him’.2

Chief among Smith’s antiquarian interests, it was noted in a slightly more barbed contemporary comment, was his ‘almost morbid curiosity in criminal cases, a trait of character that may be veiled as a love of forensic medicine. This was well seen in his museum’.3 And indeed it was. Veiled or otherwise, by 1843 Smith had collected a number of gory Bristol criminal relics and established a museum at the infirmary in which to display them. His collection included sections of the gibbet erected at the mouth of the Avon in 1741 for the executed murderer, Matthew Mahony, along with some of his bones, and the complete skeletons of three more victims of the gallows, Maria Davis and Charlotte Bobbett (hanged together for infanticide in 1802) and John Horwood (hanged for the murder of his former sweetheart, Eliza Balsum, in 1821).4 The latter three relics were easy to collect. Smith was too junior in 1802 to preside over the dissection of Davis and Bobbett. But he was present, and quick to have their bones sent to London for articulation and evisceration before showing them off in the museum in a bespoke glass case. In fact, the bones remained on public view until 2017 when they were finally removed and incinerated.5 Horwood was even easier. Smith was not only the senior surgeon responsible for his dissection, but the man who notoriously arranged for the case notes to be bound in the condemned man’s skin.

One item Smith failed to acquire – although he would surely have liked to – can be found today amongst the papers of the Town Clerk in Bristol Archives, where it has lain, largely undisturbed, for the last 260 years. It’s a bundle of criminal evidence from a long-closed but still unsolved case of murder.

When I first came across it, I hadn’t been looking for it at all. I had been working my way, fairly methodically, through the correspondence boxes of Bristol’s eighteenth century town clerks, mainly just to see what was in them since their cataloguing was rudimentary at best. As one might expect, there’s Corporation correspondence on a range of matters, petitions for freedom that multiply at every contested parliamentary election, complaints about rubbish in the streets, bundles of quarter session papers, and more. But occasionally there are also odd items that have lain undiscovered because their contents have defeated the best efforts of past archivists adequately to describe them. Like the bundle in question.

So, what is it, and how did it get there?

Let’s go back to Richard Smith who, unsurprisingly, had long been fascinated by the case it concerns. In February 1842, a year before his own death, and recognising perhaps that time for solving the mystery was running short, Smith declared himself ‘induced to leave a correct memorandum’ of the 78 year-old case ‘for the benefit of the future, and perhaps yet unborn historiographers of Brightstowe’.6

The bare facts were these. In a house on College Green in September 1764, a woman named Frances Ruscombe and her maid, Mary Champneys (or Sweet), were violently murdered. Their brutally cut and beaten bodies were discovered by a guest arriving for lunch, still warm to the touch and clearly not long dead. The house appeared to have been ransacked and it was believed the women had been robbed as well as killed, yet there was no sign of a break in and the rear door was still locked from the inside. The case caused a sensation at a time when popular anxieties about violent homicidal robberies had reached a peak, quickly making it the talk of every coffee house.7 How could the perpetrator have got into the building, savagely murdered two people and then left again, probably bloodstained and possibly carrying plundered goods, in a busy neighbourhood, in broad daylight and without alerting suspicion?

Nobody was ever prosecuted for the murder, despite an extremely generous series of rewards to tempt informers. Between them, the city magistrates, the MP Robert Nugent, Frances’s two sisters and her husband James offered a total of £260 (more than £26,000 in today’s money), and the mayor saw to it that London’s Bow Street police office circulated the reward notice in the capital.8 Over the following two months, a steady stream of suspects were taken up and interrogated on suspicion, but they were all released without charge for not a scrap of hard evidence could be found against any of them.9

Smith was fascinated by the story’s staying power. ‘Our grandfathers and grandmothers handed it down to their children as a wonderment’, he wrote, ‘In fact there is scarcely a family which can reckon back two generations, where the occurrence is unknown’.10 In 1827, Thomas De Quincey praised the anonymous killer’s matchless ‘originality of design or boldness and breadth of style’ in a satirical essay, ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’, 11 while the details were picked over anecdotally in 1884 by Joseph Leech, maverick editor of the Bristol Times, and occasionally, more analytically and comparatively in the work of Victorian criminal psychologists. The sheer horror of the Ruscombe case would never go away, it was suggested in one professional journal, because like the notorious Ratcliffe Highway murders in 1811 and the Road Hill House murder of 1860, it centred on the betrayal of ‘domesticity, and the awful feeling of insecurity carried in consequence into every household. What family was or could be safe from the intrusion of murder under such guises? Not one’.12

Worse still perhaps, Ruscombe and Sweet were murdered in one of the city’s most respectable and public neighbourhoods, frequented not only by men and women of fashion who came to the Green in numbers to promenade, but to worshippers entering or leaving the Cathedral. Indeed the crime must have been committed’, mused Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, at ‘just about the time when people were going to College Prayers’.13

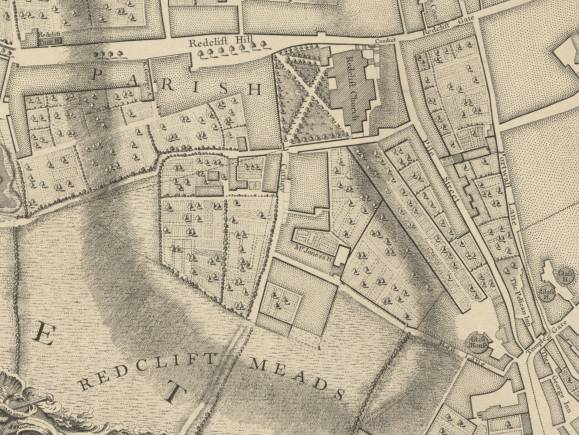

Smith well understood the need to ‘look at the locality of the murders’, and referred his readers to Richard West’s engraving (1743) of ‘The North West View of Bristol High Cross’ for evidence that

In those days there were six straggling irregular houses between the church [of St Augustine] and the Cathedral… The house of Mrs Ruscombe, which was a low pointed structure, with two slopes of common tiles, occupied the site of the present end house, of the now No. 7.

Smith pasted a copy of a slightly older drawing into one of his notebooks together with a further description of the site. ‘The last low house on the right is canonised in our history’, he wrote. ‘There resided a Mrs Ruscombe – an old lady… She had her throat cut and the servant girl her brains beat out… The whole row has been long since destroyed and the site covered by the present buildings’.

How Smith knew this to be Ruscombe’s house is far from clear. I can find no evidence of street numbering in Bristol before the publication of Sketchley’s Directory in 1775, and contemporary newspaper reports simply describe the house as being on College Green. But Smith was certain of his facts and we can perhaps assume the location was still etched firmly into the collective memory of nineteenth century Bristolians almost a century after the murders. He claimed, in fact, to have lived in a house on the site himself – probably the current No.1 Trinity Street (No.7 College Green in Smith’s day) – between 1803 and 1805. ‘And I must say’, he wrote, ‘that neither the ghosts of the murderer or murdered ever gave me the least trouble whatsoever’.14

Whether or not he was correct about the precise location of the original house, Smith will surely have been disappointed never to have obtained any interesting souvenirs from it for his museum. But then, he didn’t know where to look. He certainly knew that some valuables had been stolen because Ruscombe’s sisters, Elizabeth and Sarah Jefferies were able to confirm that much on a cursory inspection of the crime scene. The murderer had gone ‘upstairs into a Closet within the Bedchamber’, they wrote, and ‘broke open a Portmanteau Trunk’.15 Evidence as to what had been taken was unclear at first, but that was all changed by a chance discovery a day or so later. In ‘the middle of the first field in Redcliff Meads’, it was announced in the newspaper press, a bundle of items believed to be Mrs Ruscombe’s was recovered by a labouring man on his way to work. It was an odd assortment of things, ‘a green Worsted Purse, four Keys, one Reading Glass and several Receipts and Memorandums belonging to Mrs Ruscombe’. These items were ‘immediately carried to the council house’,16 where magistrates examined them for clues to the identity of the murderer.

In fact, the motley collection of items disclosed relatively little, but handwritten notes amongst the bundle of receipts, at least one of them inscribed with Ruscombe’s name, did seem to confirm that some significant sums of money had also been stolen: ‘(as appears by the papers of the deceased) 57 Guineas tied up in a Bag marked with a Figure of One and also a Silver Purse containing seven 36s Pieces and twenty-one Guineas’.17

Today of course, forensic evidence like this would be dusted for finger prints and tested for DNA. But that’s not the way criminal investigations worked in 1764. Indeed, no sooner had the College Green crime scene itself been discovered than ‘a vast concourse of people’ were reported walking all over the house, spreading bloody footprints, obscuring evidence and disturbing the bodies.18 Whatever the magistrates concluded after examining Ruscombe’s purse, keys, reading glass and receipts, they got no closer to naming a believable suspect. The bundle was put safely away by the Town Clerk and stored as potential evidence. If Richard Smith had rummaged through the drawers and cupboards of the council house in 1842, he might just have rediscovered it and added Ruscombe’s stolen possessions to his museum of curiosities. But he didn’t, and so there it has remained.

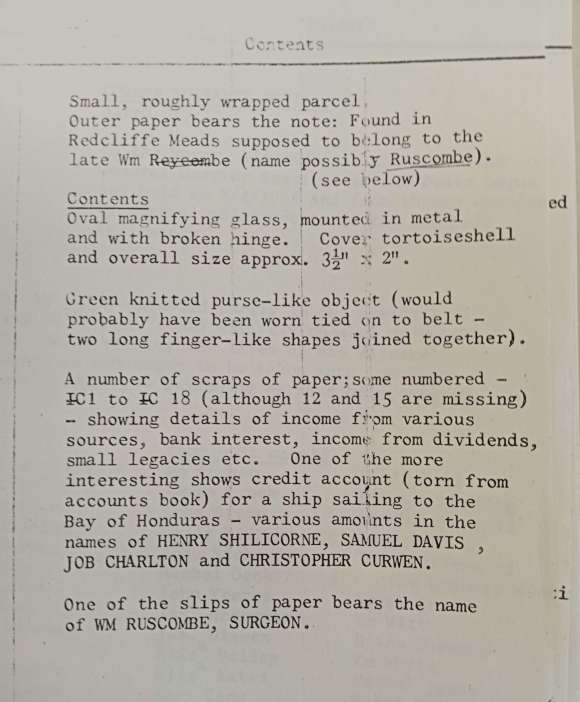

Why is this quirky bundle of evidence not better known? ‘True crime’ survivals of this kind are hardly plentiful, after all. In fact, this may well be the oldest surviving forensic material of its kind anywhere in the country. The first clue is in the original cataloguing. The bundle can be found amongst the city Administration Vouchers for 1764 (or more colloquially, the Town Clerk’s Admin Boxes), TC/Admin/Box/19/1. This is the original mid-twentieth century typescript catalogue entry:

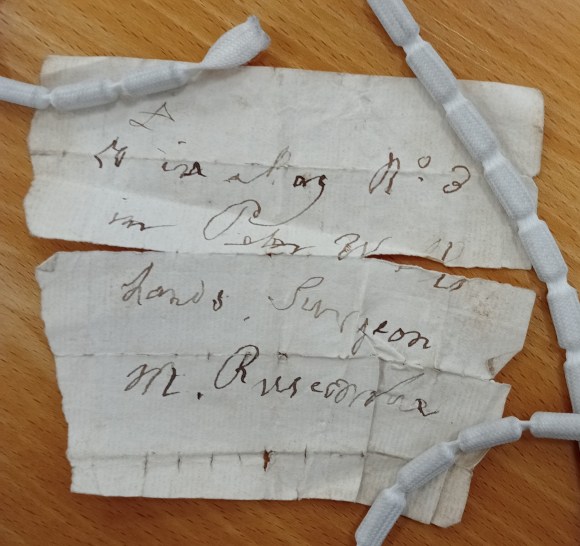

Whoever initially catalogued these items didn’t connect them to the Ruscombe case, and at first read Mrs Ruscombe as ‘Wm Reycombe’. The only manuscript in the bundle bearing Ruscombe’s name can be seen in the photograph below, which reads, ’50 in a Bag No.3 in Peter Wells hands, Surgeon. M. Ruscombe’.

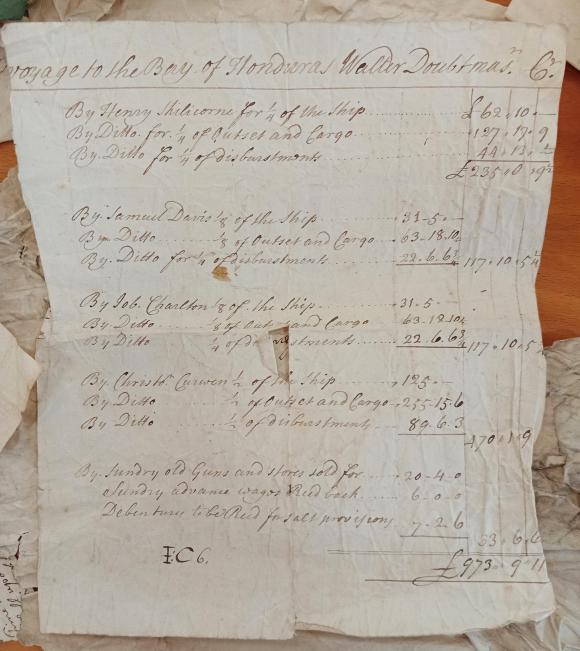

The signature ties the bundle to the family, as does the ‘credit account for a ship sailing to the Bay of Honduras’, as noted in the catalogue. The Bristol merchant, Christopher Curwen, one of the named investors in the voyage, was Frances’s first husband. She married James Ruscombe after Curwen’s death in 1749.19

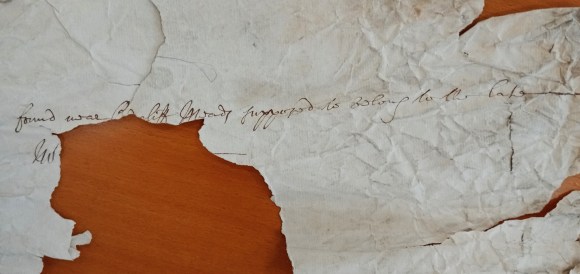

Finally, the paper wrapper everything was placed in, presumably by Elton the Town Clerk, confirms it to be the one referred to by the newspapers. The roughly written inscription reads ‘found near Redcliff Meads supposed to belong to the late Mr (or Mrs) ___________’, but the crucial name is torn off and the missing piece is not in the bundle.

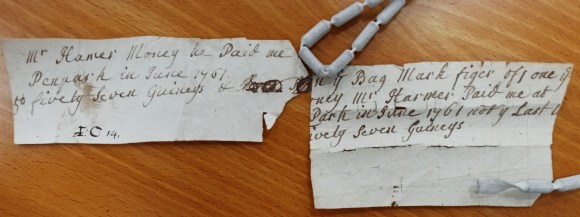

The receipts in the bundle are in a dilapidated state, some of them mere fragments. Most are just lists of payments and of interest gained on investments, but one or two concern the bagging of money, and these are the ones quoted from in contemporary press coverage, confirming it as a case of robbery as well as murder. Two fragments pieced back together include the phrase, ‘Fifty Seven Guineas & [tied up] in ye Bag Mark Figer of 1 One’.

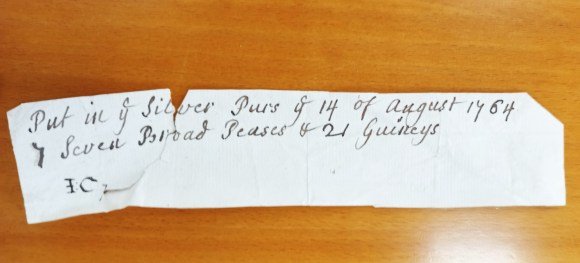

Another fragment mirroring the press reports states ‘Put in ye Silver Purs ye 14 of August 1764 7 Seven Broad Peases & 21 Guineys’. The seven ‘broad pieces’ referred to here are not identified as 3/6d coins, as they are in newspaper accounts, but the two sources are clearly referring to the same items.

Of the four keys allegedly in the bundle when it was discovered, there is now no sign. But by far the most curious objects are the empty green worsted purse (or reticule, a simple double-pocketed piece of knitwear for storing coins), and the reading glass with a tortoiseshell cover:

While it is quite possible that the purse had coins in it at the time it was stolen, the murderer’s need of a magnifying glass is less easy to comprehend. But then, since the entire bundle was presumably discarded deliberately, we might perhaps assume it was grabbed without much thought, inspected later and then rejected as valueless. We are left to consider these somewhat banal relics as representations of Frances Ruscombe’s life and social experience; a reminder that ordinary people did ordinary things but of little help in conjuring the violence with which we must try to associate them.

What are we to make of this chance discovery in the archives? Admittedly, it gets us no nearer to solving the mystery of the murder. There is no indication that the magistrates used any of the information in the bundle to open tenable lines of inquiry. If there are any clues to either motive or perpetrator in the seemingly random receipts and invoices collected here, they have nothing much to say to us now. These are silent witnesses.

Eighteenth century legal process paid remarkably little attention to motive. Murder cases tended to revolve instead around evidence of intent and provocation. Did the accused, in his or her right mind, intend the death of the victim, and if so, were there any mitigating factors? Juries might be more concerned with character, and the testimony of character witnesses, than with the perpetrator’s motive. Newspapers followed suit, devoting any number of column inches to gory descriptions of violence, often giving the impression that murder was simply a horrifying flight from reason, requiring not explanation, but prevention and equally violent punishment.20 Newspaper reports of the Ruscombe murders are jarring in their sensationalism.

Mrs Ruscombe was found dead on the stairs with her throat cut, a wound in her mouth, one of her eyes beat out, and a wound in her head so violent that her skull was beat into the brain. The maid was found in the back parlour with her head almost severed from her body, her jaw broke, a violent blow on her forehead, and her skull cleaved as with a wedge… The wounds appear as though they were given with a hammer.21

Once again, it is the evaluative distance between writing like this, and the quotidian familiarity of the material evidence in front of us; its terrible silence in the face of unimaginable barbarism, that leaves us floundering. Yet, frustratingly opaque though the Ruscombe bundle may be, it nevertheless serves as a reminder that archives hold more than historic pieces of paper and that we cannot always expect them to give up their secrets easily. In 1842, Richard Smith’s conclusion was that ‘from that moment to this, the whole matter was, and is involved in total darkness, and so will now probably remain until the Day of Judgement’.22

Perhaps so.

But let’s not be defeated. After all, there may still be pieces of evidence waiting to be found, if only by chance rather than design. Mrs Ruscombe’s four keys, for instance. Whatever happened to them, and did anyone check to see if they were keys to the exterior doors of the house? Or perhaps, rather more usefully, the case notes of the Coroner’s inquest. These, like so much else, still await rediscovery. There are questions to be answered too, for we know next to nothing about either motive or perpetrator. What of husband James, of whom we hear little except that he was away from home at the time. And why would anyone go to such frenzied lengths to overcome two women, one of whom was at least 64 years old, and then make off with a reading glass and a bundle of financial reckonings? Two hundred and sixty years after the fact, perhaps it’s time to reopen the case.

References

- I would like to thank Bristol Archives for permission to include images of their documents in this story. All images subject to copyright. For their comments on earlier drafts of this piece, I thank Evan Jones, Anne Lovejoy, Jonathan Barry, Roger Leech and Andy Foyle. ↩︎

- Bristol Times and Mirror, 28 January 1843. ↩︎

- Notes and Queries, 27 September 1856, p. 250. ↩︎

- For Smith’s museum and the fate of Mahony’s gibbet in particular, see Steve Poole and Nicholas Rogers, Bad Blood in Georgian Bristol: The Murder of Sir John Dineley (Redcliffe Press: Bristol, 2022), pp. 85-6, 100-103. ↩︎

- Nikita Marryat, ‘People, Patients and Preparations: Post-Mortem Journeys and the Status of Human Remains in the Medical Museum of Richard Smith Junior, (1772-1843) at the Bristol Infirmary’, M.Phil., University of Bristol, 2019, pp. 89-93. ↩︎

- Smith’s account of the murder was published as a short pamphlet The Murder of Mrs Frances Ruscombe and her Maid in College Green AD 1764 (Bristol, 1842), and then republished in Tales From the Bristol Mirror (Bristol, 1842), pp. 10-15 and later in Curiosities of Bristol, 10 (June 1854), pp. 72-3 and 11 (July 1854), pp. 77-8. There are also copies in Bristol Archives, 9733/3 and in Richard Smith’s papers, Bristol Archives, 14754. ↩︎

- See Richard M. Ward, Print Culture, Crime and Justice in 18th Century London (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 173-6. The mid-century fear of homicidal robbery, stoked regularly by the newspaper press, was far greater than its actual occurrence, but it drove the Murder Act (1752), under which murderers were denied Christian burial, leaving them to the mercies either of the surgeons or the gibbet. ↩︎

- Public Advertiser 6 October 1764. For the readiness of Fielding’s office to assist provincial authorities see J. M. Beattie, The First English Detectives: The Bow Street Runners and the Policing of London, 1750-1840 (Oxford: OUP, 2012), 85-6. Fielding remained alert to the case and sent some advice to the mayor about one of the suspects in 1765: Oxford Journal 4 May 1765. ↩︎

- Lloyds Eve Post 30 Nov-2 Dec; London Chron 8-11 Dec; 2-4 April 1765. ↩︎

- Richard Smith, op cit. ↩︎

- Thomas De Quincey, ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’, Blackwoods Magazine, February 1827. ↩︎

- Joseph Leech, ‘The Mystery of College Green’, in Brief Romances From Bristol History (Bristol, 1884), pp. 203-4; ‘The Road Murder Psychologically Considered’, The Medical Critic and Psychological Journal (July, 1861), pp. 437-8. ↩︎

- Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal 29 September 1764. ↩︎

- That James Ruscombe definitely lived somewhere on College Green from at least 1757-8 is confirmed by his payment of watch rates on the property, and support for Smith’s assertion that the Ruscombe house was a relatively modest structure may be seen in the scale of charges. Ruscombe paid considerably less than most of his neighbours, so it is unlikely to have been the very substantial house now designated as No.1 Trinity Street. See Bristol Archives, F/WR/StM, ‘Watch Rates for St. Michael including St. Augustine, 1755-1834’. According to the National Heritage List, the four Georgian town houses currently occupying the space between the Marriott Hotel and the Cathedral were built c.1760. So we may surmise that they replaced the Ruscombe house shortly after the murders. For Smith’s detailed descriptions of the original house, and his claim to have once lived on the site, see his notebook, Bristol Archives, 14754/1, and published account, The Murder of Mrs Ruscombe and her Maid. Joseph Leech believed Ruscombe’s house stood undisturbed until 1865 when it was demolished to make way for the Royal Hotel (now the Marriott). Leech, ‘Mystery of College Green’, pp. 203-4. See also Andrew Foyle, Bristol, Pevsner Architectural Guides (Yale, 2004), p. 129 for the probable age of the surviving row. ↩︎

- Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal 6 October 1764. ↩︎

- Bath Chronicle 4 October 1764. ↩︎

- Public Advertiser 6 October 1764. ↩︎

- Bath Chronicle 4 October 1764. ↩︎

- D. P. Lindegaard, ‘Mrs Frances Ruscombe and her maid, Mary Champness, otherwise Sweet: a double murder at College Green‘, Bristol History blog (2 June 2021). ↩︎

- See J. M. Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England, 1660-1800 (Oxford: OUP, 1986), pp. 77-99. ↩︎

- Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal 29 September 1764; Lloyd’s Evening Post 28 September – 2 October 1764. ↩︎

- Smith, op cit. ↩︎